Everyday People Can Affect Change in Their Community

Amy Kenreich has not always been a bike advocate. In fact, she says that she fell into bike advocacy almost by chance in 2017 when she helped organize a bike rodeo at her childrens’ elementary school. The rodeo was a success with both kids and adults showing up to have fun on their bikes. This got her thinking. Why weren’t more people riding their bikes to the grocery store or to a coffee shop on a regular basis?

About this time, a friend of Amy’s encouraged her to apply to the Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Committee (MBAC). Amy felt that Denver had some problems to solve with its bike network, and that family biking was under-represented on the committee. This led her to apply, and she now serves on the committee. Amy is advocating for change to make cycling safer in Colorado and has been a strong supporter of adding protected bike lanes to S. Marion St. Parkway.

In 2017, Denver voters approved a 10-year, $937 million bond, which is called the Elevate Denver Bond Program, to improve Denver’s infrastructure: namely, roads, sidewalks, parks, recreation centers, libraries, cultural centers, public-owned buildings, health and safety facilities. The Elevate Bond Program dedicates $18 million to the design and construction of 50 miles of neighborhood bikeways and protected bike lanes, so-called high comfort bikeways. The S. Marion St. Parkway High Comfort Bikeway project is one of 500 projects included in the bond program. It will add a protected bike lane on S. Marion Street from E. Bayaud Avenue to E. Virginia Avenue. South Marion St. Parkway links to other bikeways (Downing St Path, Cherry Creek Trail, Washington Park Loop, E Exposition Ave, S Franklin St), provides routes to schools (Steele Elementary, South High School, DU), and makes parks accessible according to the City and County of Denver.

A Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) survey of Metro-Denverites (2018), concluded that 59 percent are interested in riding their bikes on Denver streets but are concerned. However, 75 percent indicated that they would ride a bicycle if they had the option of a network of high comfort bikeways according to the survey results. A high comfort bikeway includes a horizontal buffer, a vertical element such as flexposts or planters, and high visibility markings of conflict areas such as intersections. The protected bikeways provide a buffer between the cyclist and passing traffic.

Studies show that protected bikeways have many advantages. Among them are:

Reducing/eliminating dooring issues

Providing greater safety, reducing number of collisions, resulting in fewer injuries

Reducing/eliminating parking and loading conflicts

Promoting more biking and less driving

Reducing traffic congestion

Boosting economic growth

Amy had a difficult time understanding why anyone would oppose a protected bike lane, especially in front of an elementary school. She lives four blocks away from this project and often takes her kids to the playground at Steele Elementary. She also rides S. Marion Street Parkway to reach the Cherry Creek Trail.

When Alexis Bounds was struck and killed, it made Amy mad and terrified. “Because I have been on the MBAC and because I know about Vision Zero, I just couldn’t sit by and do nothing,” she says.

First, she attended a meeting where discussions were held about the protected bike lane on S. Marion Street Parkway. “Unfortunately, the first public meeting turned into an ‘us vs. them’ debate between neighborhood bicyclists and residents who live in the tower apartment buildings at the base of S. Marion Street Parkway,” she says.

The arguments that Amy heard against the S. Marion Street Parkway Bikeway were:

It is a beautiful street, and I think the protected bike lane will ruin that.

I think it is fine the way it is (even after Alexis’ death).

It could interfere with Steele Elementary school loading.

Marion has a historic designation, and it is against those guidelines to put in vertical separation.

I think this will make cyclists go even faster, and one of these days they are going to run over my elderly mother.

I think it will interfere with loading at my building.

I think it will prevent emergency services from accessing my building.

Amy says that it was especially frustrating to keep up with the mis-information:

But cyclists break the law! (Actually cyclists and drivers break the law at the same rate.)

“Our” street is perfect the way it is. (No one person owns the street in front of their home.)

It will lower my property value. (False, according to the National Association of Realtors)

It will remove parking. (No plan ever included removing parking.)

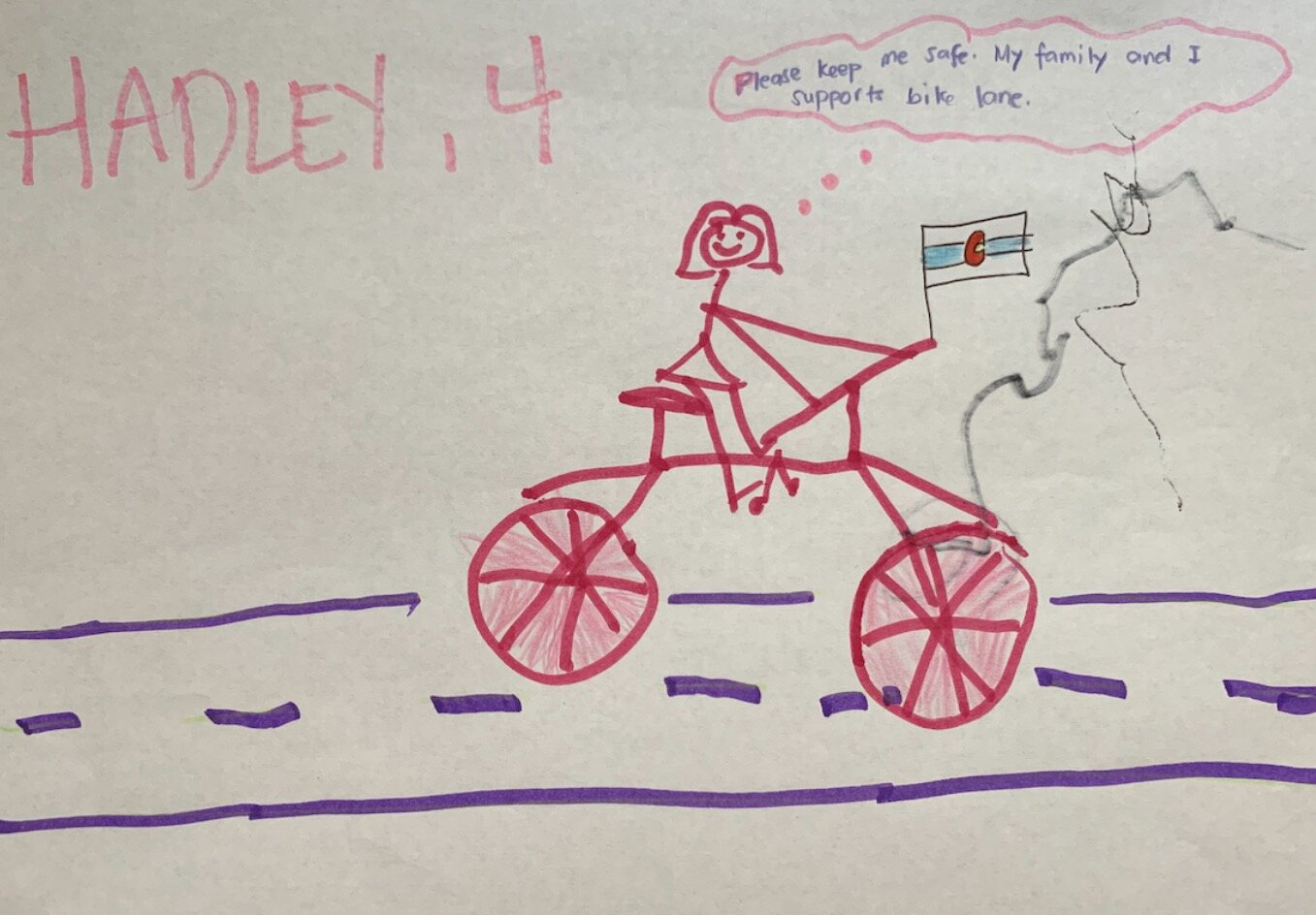

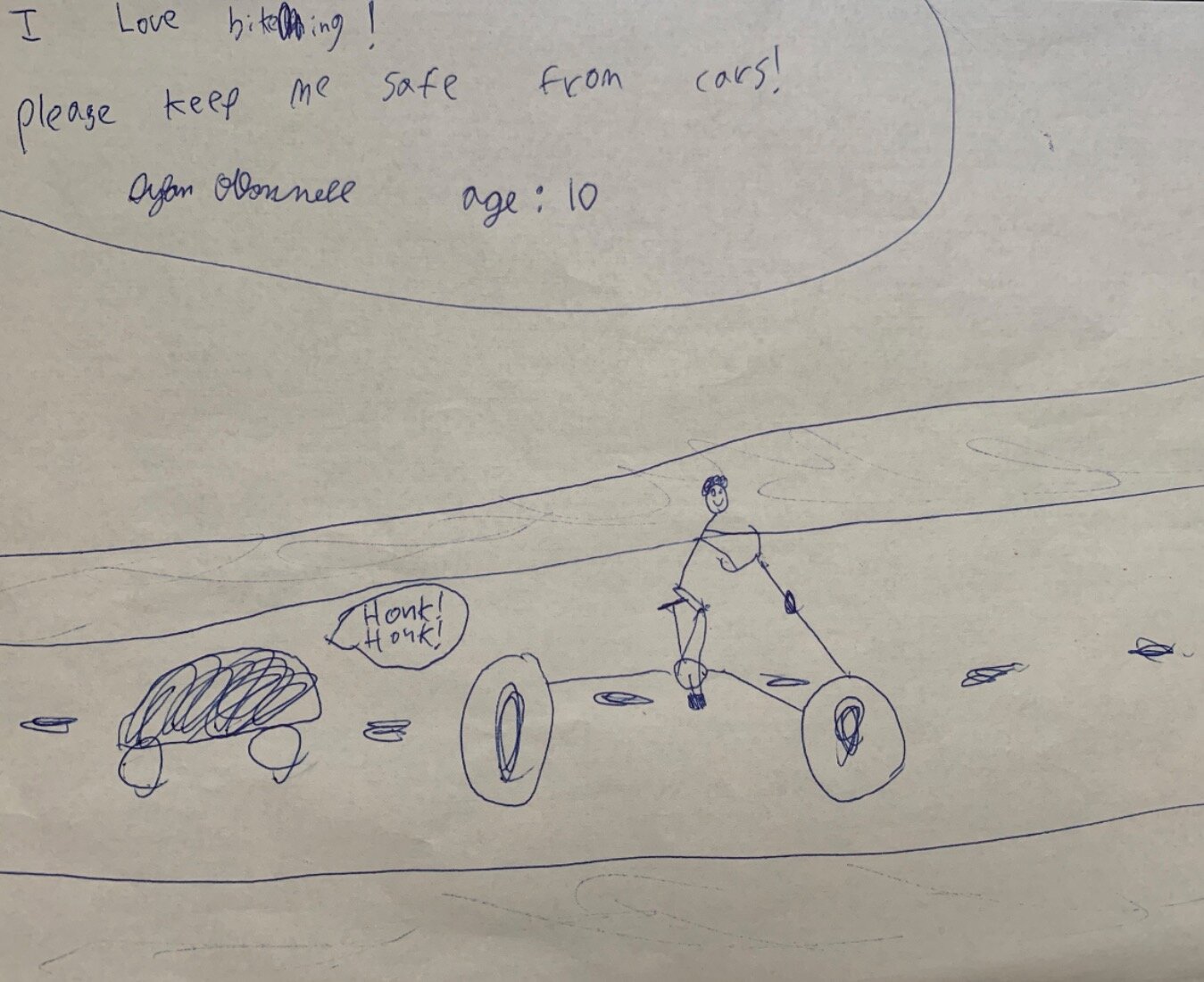

Soon after, Amy received an invitation to meet with District 6 City Councilman Paul Kashmann. In preparation for their meeting, Amy conducted an experiment at the Washington Park playground. She took her kids there along with some paper and markers. While they played, Amy spoke to parents and caretakers about the planned protected bike lane. There was an overwhelmingly positive reaction to the project. She left the playground with letters from parents and drawings from children.

Amy brought some of her favorites to Kashmann to illustrate the support for the project and also to highlight the obvious—who this protected bike lane was really going to protect. “In my opinion, the voices opposed were forgetting about some of our most vulnerable road users—children trying to get to school,” explains Amy.

When she learned that there was a petition circulating against the project, Amy decided to reach out to the person orchestrating it. She met with the concerned neighbor in her home, and together they watched the street below from the woman’s balcony near the top of the north tower. As the neighbor pointed out bicyclists who rolled through the stop signs, Amy also saw cars roll through them without stopping. Her goal was to listen to her nieghbor. “I truly thought that if she met me—one of those cyclists she described as irresponsible—and if I listened to her, that she would see the humanity of the issue at hand.”

Amy also wanted to make sure she heard and understood the neighbor’s perspective. If nothing else, this was an opportunity for Amy to learn where she was coming from and correct any inaccuracies.

Over the summer, Amy met one-on-one with more people opposed to the project and joined a stakeholder meeting held by the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI). She spoke to many more people who were in favor of the project. She begged each one to come to the next public meeting.

As time went on, Amy got more and more involved. She had the opportunity to speak to one of the local news stations about the project. Amy rode her two children over to the Steele Playground, and she and her friend, Tenly Williams, told the reporter how excited they were for the students who want to bike to Steele Elementary and for all the commuters who would ride through this area to reach the Cherry Creek Trail path. The majority of students at Steele live within a 1.5 mile radius of the school.

Amy and fellow bike advocate Adam Meltzer were invited to speak at the East Washington Park Neighborhood Association meeting. They put together a one-page handout that collated the major project info and corrected the “fake news” floating around about the project. Her goal that night was to provide facts and answer questions. The short presentation turned into a 2.5 hour question/answer session.

On the morning of Alexis’ death, Amy was part of a Denver Streets Partnership video that was made to promote the benefits of the project. “I was in shock 24 hours later when I returned to S. Marion Street to talk to a couple of news stations about the crash,” says Amy. The petition organizers were on the scene, too. Amy’s message was quite different from theirs. One of them told a reporter, “I just don’t think they need that protection” while standing on the corner where Alexis had been killed.

The next day, Amy got an email from some of the petition organizers explaining that if only the city would put in a stop sign, this tragic “accident” could have been prevented. At that point, Amy had to ask them for some space. It was more than she could handle.

Later in the fall, Amy presented a quick update at the Steele Elementary PTA meeting. She did not get many questions, and it seemed that most people either did not have a strong opinion or were content with the project plans.

Finally, with the help of Tenly Williams, Amy designed some flyers advertising the second public meeting and sent them out to other bike advocates to place on bikes throughout the area.

Early in November 2019, the city held a second public meeting about this project. The design was at 60 percent at that time, and they again collected feedback from attendees. The room was full; this time the crowd included a majority of people who were in favor of the project. The city is currently finalizing the design and construction is planned for 2020.

Amy encourages people in Denver to follow the Bicycling in Denver page. For a list of upcoming public meetings, check out News and Updates. “One of the best things you can do is attend these meetings and make your voice heard,” says Amy. Another way you can help is to submit feedback on the same site. DOTI really does read and tally up all comments that come in on a project. For the S. Marion St. Parkway Bikeway project, the city showed a slide of all the types of feedback that came in, and it clearly showed that the number one priority was the safety of bicyclists and pedestrians. “Your voice matters, and it doesn’t take much time to make sure it’s heard.”

Another site to watch is the Denver Bicycle Lobby. They post the Denver bike lane public meeting dates on their site and also host meetups and organize efforts to support bicycle advocacy in Denver.